- 2018 Individual Inductee -

Mary Ann (Ball) Bickerdyke

The pious deeds of Russell County’s Mary Ann “Mother” Bickerdyke are worthy of the many legends that surround her astonishing life of service to America’s veterans and the poor. In her own lifetime she was known as the American Florence Nightingale, and was so beloved in her adopted state that she was acclaimed the Patron Saint of Kansas.

Mary Ann Ball was born on a farm near Mount Vernon, Knox County, Ohio on July 15, 1817. She was the daughter of Hiram and Ann (Rodgers) Ball. Her mother died in December 1818 when Mary was seventeen months old. Mary, her sister, and her mother’s two children from a previous marriage were sent to live on their grandparents’ farm at Mansfield, Richland County, Ohio. Upon their passing Mary went to live with her Uncle Henry Rodgers. Mary’s father Hiram remarried in 1821 and moved to Belleville, Ohio, some ten miles from Mansfield.

Throughout her childhood Mary received only a very basic education. At the age of sixteen she moved to Oberlin, Ohio. She later returned to live with her uncle on his farm in Hamilton County, near Cincinnati, Ohio. No one is quite certain about Mary’s life during the decade of 1837 to 1847. It is thought that she traveled with an aunt, evangelist Lydia Brown, and lived for a time in Cleveland, Ohio working as a domestic servant. Mary may have helped care for the victims of the cholera epidemics that ravaged Cincinnati in both 1837 and 1849.

On April 27, 1847 Mary married Robert Bickerdyke, a widower with three children who worked as a mechanic, a sign painter, and a bass viol player. Together they had four children of their own: Robert, born in 1849 but lived only a few minutes; James; Hiram; and daughter Martha (Mattie), born in 1858 and died during a cholera epidemic in 1860. The family first lived in Cincinnati and in they moved to Galesburg, Illinois. Upon her husband’s sudden death in March 1859 Mary was left a widow with three young children, whom she supported by working as a laundress, housekeeper, and nurse.

In June 1861 Mary was at church when the pastor, read a letter to the congregation that told of the poor conditions of the military hospital in Cairo, Illinois. The congregation was moved by the letter and gathered five hundred dollars and medical supplies to send to Cairo, but they needed someone to deliver them. Another church member elected Mary, and she proudly accepted. Mary was appalled at the hospital conditions and went to work cleaning up . She told the men how to keep it clean and promised to check on them. At first they were very rude to her, but she ignored them and went about her work. In time the soldiers recognized her tireless efforts on their behalf and began affectionately calling her "Mother".

In Cairo Mary used the supplies to establish a hospital for the soldiers. She spent the remainder of the war traveling with various Union armies, establishing more than 300 field hospitals to assist sick and wounded soldiers. At first Mrs. Bickerdyke was only a “volunteer nurse,” having no authority whatever and had to depend upon her nerve for almost everything. She was afterwards appointed an agent of the Sanitary Commission which gave her better standing. She was one of the commission’s best agents, being gifted with first class executive ability. Where “red-tape” interfered she cut it. If drunken doctors attempted to interfere with her they came to grief. She commonly risked her own life during battles while searching for wounded soldiers. Once darkness fell she would carry a lantern into the disputed area between the two competing armies and retrieve wounded soldiers.

The battle of Shiloh found the hospitals poorly prepared to take care of the thousands of wounded, among whom Mother Bickerdyke, as the soldiers had affectionately named her, passed like a ministering angel. This was followed by Corinth and other engagements until she finally landed at Memphis where there were hundreds of soldiers sick in the hospitals. Finding great difficulty in procuring milk and eggs for the hospitals she obtained a furlough for 30 days and went north and returned with a drove of cows and a large flock of hens donated by the people for hospital use.

Both Generals Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman admired Bickerdyke for her bravery and for her deep concern for the soldiers. To assist the soldiers, Mary gave numerous speeches across the North, describing the difficult conditions that soldiers experienced and solicited contributions. General Grant sent Mary to Memphis, Tennessee where she was put in charge of the Gayoso Block Hospital. It soon became known as Mother Bickerdyke’s Hospital. After the fall of Vicksburg she was attached to Sherman’s command and was highly appreciated by that great general, who is said to have replied to an officer who made complaint about her that he could do nothing for him, as Mother Bickerdyke, well, "she outranks me".

While traveling with the troops Mary suffered the same hardships and struggles as the soldiers did. The extreme cold weather, poor conditions and lack of good food and supplies was hard on everyone. When Atlanta was captured by the Union on September 2, 1864 Mary helped evacuate the wounded from the hospitals.

Mary left the service as poor in purse as she entered it. She had handled a great deal of money, but none of it stuck to hers. Her labors had been continuous and severe and she had earned and needed a rest. But she had to go to work to earn her living. Mary cared for wounded soldiers at the Home for the Friendless in Chicago, Illinois. She soon saw that the young men, many disabled and without careers, were desperate for employment. Hearing of land for homestead in Kansas Mary took a train west in 1867 and took up a claim of 160 acres of land in Barton County. At Salina, Kansas Mary convinced the Kansas Pacific Railroad to build a boarding home, the Salina Dining Hall, which could sleep 33 veterans and feed 110. In 1869 the railroad closed the boarding house and Mary decided to leave Kansas for New York, where she took a position on the Protestant Board of City Missions and worked to clean up the city’s slums. From there she went to Chicago performing the same task. While engaged in the city missionary work in Chicago her sympathies became aroused by the large number of soldiers who were stranded in that city unable to obtain work and destitute of means of living. She formed a plan to get them to go west and take up land. With this object in view she started west into Kansas and came as far west as Great Bend. Having found locations in Kansas which suited, she succeeded in making arrangements with the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad for two years of free transportation for the veterans and their families. She helped to settle over 300 families in and around Saline, Barton, Russell, Lincoln, Ellsworth, Ottawa, Stafford, and Rice Counties in Kansas.

While she was in New York her sons had started a farm on her homestead land near Great Bend, Kansas. She came back to Kansas to live with them in the summer of 1874 – just in time for the great grasshopper invasion that destroyed crops everywhere in western Kansas. Mary then traveled across the United States and gave hundreds of speeches, asking for help for the nearly destitute settlers. In all she raised some 200 boxcar loads of grain, food and clothing in contributions to the cause.

Mary’s two years’ labor in this work broke down her health and in 1876 she went to California to recuperate. In San Francisco she was engaged in the street missionary work and labored very hard among the poor, the destitute and the vicious. The manner in which Mary exposed herself to danger alarmed her friends who asked her how she could take such risks. Her reply was, “Why, don’t you know that every policeman on duty was one of my boys?” – meaning an old soldier.

In 1883 Mary received an appointment to a position in the U. S. Mint. She remained there until 1887 when she resigned in order to nurse and care for her daughter, who died in Covington, Kentucky. Mary then lived with her son James in Bunker Hill, Kansas from July of 1887 to December 1888, when they both moved to house in Russell, Kansas, located on the northwest corner of 7th and Lincoln Streets until 1894. James served as Russell County Superintendent of Schools at this time. While Mary lived in Russell she made daily rounds to visit and advocate for the personal needs of the homebound and sick veterans, “her boys”, who needed nursing care. One veteran from San Francisco came to live in Mary’s home to be nursed by “Mother” until his death from cancer. He lies buried in the Russell Cemetery.

Mary and James moved in August 1895 from Russell to Salina, where James taught for a year as a professor at Kansas Wesleyan College. Later that year the Kansas State Historical Society honored Mary with a ceremony acknowledging her service to the people.

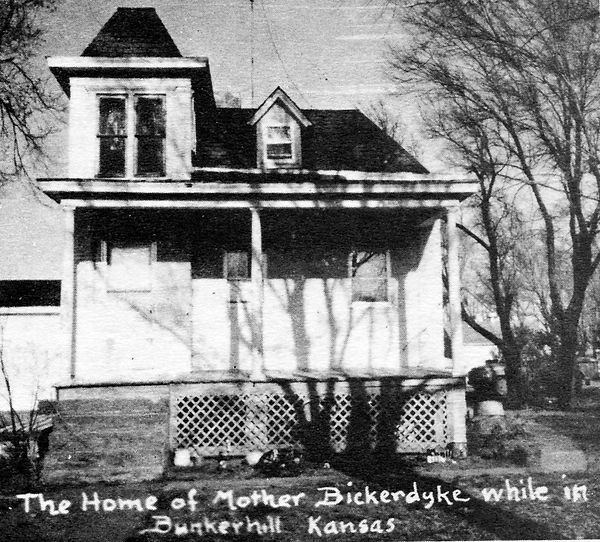

In 1896 Mary and James returned to Bunker Hill. The first residence Mary ever owned was given to her on her 80th birthday in Bunker Hill by the local veterans she had served so well all those years. On July 9, 1897 a statewide celebration for Mother Bickerdyke Day was held in Kansas. That same year the Woman’s Relief Corps named its Ellsworth, Kansas facility for wives and daughters of Civil War veterans the Mother Bickerdyke Home and Hospital in recognition of her many years of humanitarian service.

Shortly before Mary’s passing, Galesburg, Illinois Post No. 45 of Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) asked her for the honor to conduct her funeral and burial service when that time came. To this she agreed. Mary Ann Bickerdyke passed quietly away on November 8, 1901, in Bunker Hill at the age of 84 years. Her first memorial services were conducted by the G.A.R. Post in Bunker Hill, as the G.A.R. members of Kansas felt that she was one of their own since Mary had lived in the state for 34 years. Mary’s remains were then shipped to Galesburg by rail and were accompanied by her son, two members of the Bunker Hill G.A.R. Post, and a large flag contributed by the Post. The funeral was held in the Central Congregational Church, of which Mary had been a member when she lived in Galesburg.

“I have known Mother Bickerdyke many years and loved her as all of the boys have loved her. I have seen her at many reunions and there has always been something sympathetic about her. I remember that on the Southern battlefields when the cannons and the muskets stopped, Mother was there and despite the rain, mud and cold she went everywhere to bring relief to the soldiers. There are soldiers in every state who owe their lives to her. There is no name in Kansas more respected, loved and venerated than that of Mother Bickerdyke.” – Kansas State Senator Harry Pestana, speaking in Galesburg at the funeral of Mary “Mother” Bickerdyke.

Mary was laid to rest in the Linwood Cemetery beside her husband Robert and infant daughter Martha. On May 22, 1906, a bronze monument to Mother Bickerdyke’s memory was unveiled on the grounds of the county courthouse in Galesburg before an estimated crowd of 8,000 people.

The fame of “Mother” Bickerdyke derives from her army service. But she regarded her services among the poor and destitute in the cities of New York, Chicago and San Francisco as equally, if not more laborious and important.

In 2010 Mary Ann “Mother” Bickerdyke was accorded the honor of being a finalist in the 8 Wonders of Kansas People contest sponsored by the Kansas Sampler Foundation.

The former Lutheran church where James and Mary Bickerdyke worshiped in Bunker Hill is now the Mother Bickerdyke Museum and preserves many historic artifacts of their lives.

It is with much-deserved acclaim that Mary Ann "Mother" Bickerdyke be accorded a selection to the First Class of the Russell County Kansas Hall of Fame.

SOURCES:

The Journal, Russell, Kansas, July 23, 1897

Russell Record, Russell, Kansas, November 16, 1901

Washington Times, July 23, 2005

L. P. Brockett and Mary C. Vaughn, Woman’s Work in the Civil War: A Record of Patriotism, Heroism, and Patience (1867)

Sarah E. Henshaw, Our Branch and Its Tributaries: Being a Story of the Work of the Northwestern Sanitary Commission and Its Auxiliaries, During the War of the Rebellion (1868)

Margaret B. Davis, The Woman Who Battled for the Boys in Blue: Mother Bickerdyke (1886)

Mary Livermore, My Story of the War (1887)

Marla Snow, transcribed by, American Women Fifteen Hundred Biographies, Volume 1 (1897)

Florence S. Kellogg, Mother Bickerdyke as I Knew Her (1907)

Nina Brown Baker, Cyclone in Calico: The Story of Mary Ann Bickerdyke (1952)

Martin Litvin, The Young Mary, 1817-1861: Early Years of Mother Bickerdyke, America’s Florence Nightingale, and Patron Saint of Kansas (1977)

www.faqs.org/health/bios/32/Mary-Ann-Ball-Bickerdyke.html#ixzz2DqufZuzn, “Mary Ann Ball Bickerdyke Biography (1817-1901)”

www.historyswomen.com/socialreformer/Bickerdyke.html, Christina Lewis, “Mother Bickerdyke: A Civil War Nurse”

www.anb.org/view/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.001.0001/anb-9780198606697-e-1200074, American National Biography: Sarah H. Gordon, “Bickerdyke, Mary Ann Ball (19 July 1817–08 November 1901)”

www.ohiobio.org/health/bickerdyke.html

Mary Ann Bickerdyke gravestone, Linwood Cemetery, Galesburg, Illinois.

Mother Bickerdyke Monument, Knox County Courthouse grounds, Galesburg, Illinois.

Mother Bickerdyke Monument, Knox County Courthouse grounds, Galesburg, Illinois.