2017 Individual Inductees to the Kansas Film & TV Hall of Fame:

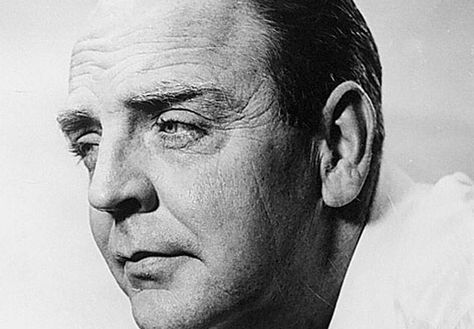

William Inge (1913-1973)

Independence, Kansas

William Motter lnge, playwright, novelist, and actor, was born on May 3, 1913, in Independence, Kansas. He was the second son of traveling salesman Luther Clay Inge and Maude Sarah (Gibson) Inge and the youngest of five children. William graduated from Independence High School in 1930 and went on to attend Independence Junior College. Inge graduated from the University of Kansas in 1935 with a Bachelor of Arts Degree In Speech and Drama. Confused with what he wanted to do with his life, Inge went back to Independence, where that summer he worked as a laborer on the state highways. After that he went to Wichita, where he worked as a news announcer. In 1937-1938 Inge taught high school English and Drama in Columbus, Kansas. From 1938-1943 Inge was a member of the faculty at Stephens College in Columbia, Missouri. In 1943 Inge moved to St Louis, Missouri, where he worked as the drama and music critic for the St Louis Times. Inge became acquainted with the great playwright Tennessee Williams, and a performance of Williams' play "The Glass Menagerie" compelled Inge to try to write his first play, "Farther Off From Heaven". Inge began teaching at Washington University In St. Louis and began serious work on turning a fragmentary short story Into a one act play. "Come Back, Little Sheba" earned Inge the title of most promising playwright of the 1950 Broadway season.

In 1952 Paramount Pictures released the film version of Come Back, Little Sheba starring Shirley Booth and Burt Lancaster. Inge's next play, "Picnic", opened In 1953 at The Music Box Theatre In New York City. ''Picnic" won Inge a Pulitzer Prize, The Drama Critic Circle Award, The Outer Circle Award, and The Theatre Club Award.

Inge's next success came In 1955 when "Bus Stop" opened at The Music Box Theatre in New York City. The film version of Bus Stop was released by Fox In 1956 with Marilyn Monroe, Don Murray and Eileen Heckart in starring roles. That same year Columbia Pictures released the film version of Picnic, starring William Holden, Kim Novak and Rosalind Russell, and filmed on location in central Kansas.

Inge's fame continued to grow as "The Dark at the Top of the Stairs', a reworking of his first play "Farther Off From Heaven", opened on Broadway In 1957. It Is considered to be Inge's finest play, and one in which he draws most directly from his own past. The 1960 film version starred Dorothy McGuire, Robert Preston, Shirley Knight, Eve Arden, and Angela lansbury. Inge became noted for finding the poetry and tragedy In small lives, for capturing the essence of Midwestern middle-class life.

In 1959, Inge's play "A Loss of Roses" opened to poor reviews and closed after a three week run. Always insecure and somewhat unstable, Inge was devastated by the criticism. The next year Inge's first movie screenplay, Splendor In the Grass, was filmed in New York, starring Natalie Wood, Pat Hingle and newcomer Warren Beatty. It also featured Inge's only feature film acting role, the part of Reverend Whitman. Splendor in the Grass was a triumph for Inge and won him the 1961 Academy Award for Best Screenplay. His next two plays, 1963's "Natural Affection" and 1965's "Where's Daddy?", were unsuccessful. He left New York In 1963 at the age of fifty and moved to California, resuming his teaching career In 1968 at the University of California at Irvine, but he

became increasingly depressed and quit in 1970. He last two projects were both novels, Good Luck, Miss Wyckoff (1970) and My Son Is a Splendid Driver (1971), a largely autobiographical account of Inge's boyhood years.

Severe depression caused Inge to take his own life at age 60 on June 10, 1973 at his home in Hollywood, California. Inge was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in his hometown of Independence, Kansas. His headstone epitaph reads simply, PLAYWRIGHT.

The annual William Inge Theatre Festival began in 1982 on the campus of Independence Community College in Independence, where the William Inge Center for the Arts is the cultural hub for college and civic activities. In 2009 Inge was named one of the 8 Wonders of Kansas People, a lasting honor acknowledging the great legacy of this gifted Kansan.

* * * * * *

DlD YOU KNOW that the small town of Independence had a profound Influence on the young William and he would later attribute his understanding of human behavior to growing up in this small town environment. "I've often wondered how people raised in our great cities ever develop any knowledge of humankind. People who grow up in small towns get to know each other so much more closely than they do in cities," said Inge. William would later use this knowledge of small town life In many of his plays, most of which revolve around characters who are clearly products of small towns like Independence. He became known as "The Playwright of the Midwest".

Short Plays:

1953: Glory in the Flower

The Killing

The Love Death

The Silent Call

Bad Breath

Morning on the Beach

Moving In

A Murder

Plays:

Farther Off From Heaven

1950: Come Back, Little Sheba

1953: Picnic

1955: Bus Stop

1957: The Dark at the Top of the Stairs (a reworking of Farther Off From Heaven)

1959: A Loss of Roses

1962: Summer Brave (a reworking of Picnic)

1963: Natural Affection

1966: Where's Daddy?

1973: The Last Pad

Off the Main Road

Film and TV:

1961: Splendor in the Grass

1963: All Fall Down

1964: Out on the Outskirts of Town

(a reworking of Off the Main Road)

1965: Bus Riley's Back in Town (as Walter Gage)

Novels:

1970: Good Luck, Miss Wyckoff

1971: My Son Is a Splendid Driver

William earned the following notable honors both prior to his death in 1973 and after:

1953 - Pulitzer Prize for Drama for the play Picnic

1956 - Nominated for Tony Award for Best Play, for Bus Stop

1958 - Nominated for Tony Award for Best Play, for The Dark at the Top of the Stairs

1962 - Academy Award for Best Screenplay, for Splendor in the Grass

* * * * * *

Hattie McDaniel (1898-1952)

Wichita, Kansas

Hattie was born on June 10, 1893, in Wichita, Kansas, the youngest of 13 children born to former slaves Henry McDaniel, who fought in the Civil War with the 122nd United States Colored Troops, and Susan Holbert, a singer of religious music. Her father was a Baptist minister, carpenter, banjo player, and minstrel showman, eventually organizing his own family into a minstrel troupe. Henry moved their growing family to Denver, Colorado, in 1901.

Hattie was one of only two black children in her elementary school class in Denver. She sang at church, at school, and at home; she sang so continuously that her mother reportedly bribed her into silence with spare change. Before long Hattie was also singing in professional minstrel shows, as well as dancing, performing humorous skits, and later writing her own songs.

In 1910 Hattie left school in her sophomore year at East Denver High School and became a full-time minstrel performer, traveling the western states with her father's show and several other troupes. The shows presented a variety of entertainment that poked fun at black cultural life for the enjoyment of mostly white audiences.

When Hattie's father retired around 1920, she joined Professor George Morrison's famous "Melody Hounds" on longer and more publicized tours. She also wrote dozens of show tunes such as "Sam Henry Blues," "Poor Wandering Boy Blues," and "Quittin' My Man Today."

Hattie's first marriage ended brutally in 1922, when her husband of three months, George Langford, was reportedly killed by gunfire. Her career was much better, including a first radio performance in 1925 on Denver's KOA station. Hattiewas one of the first black women to be heard on American radio. She became a huge vaudeville star in her day as a singer and dancer. From 1926 to 1929 she recorded many of her original songs for Okeh Records and Paramount Records in Chicago.

In 1929 Hattie was left without a job due to the Great Depression, so she went to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and found work at Sam Pick's Club Madrid—as a bathroom attendant. Eventually she became a performer there and remained at the Club Madrid for about a year. Next Hattie went to Hollywood, California, where her brother and sister lived. Sam and Etta McDaniel had already played small roles in a number of motion pictures. Sam McDaniel had a regular part on the KNX (Los Angeles, California) radio show "The Optimistic Do-Nuts" and was able to get Hattie a small part, which she promptly turned into a big opportunity. Hattie eventually became a hit with the show's listeners.

A big break came for Hattie in 1934, when she was cast in the Fox production of "Judge Priest". In this picture Hattie was given the opportunity to sing a duet with Will Rogers (1879–1935), the well-known American humorist. Her performance was well received by the press and her fellow actors alike.

In 1935 Hattie played Mom Beck in "The Little Colonel". A number of African American journalists objected to Hattie's performance in the film. They charged that the character of Mom Beck, a happy black servant in the Old South, implied that black people might have been happier as slaves than they were as free individuals. This movie marked the beginning of Hattie'slong feud with the more progressive elements of the African American community.

Once established in Hollywood, Hattie found no shortage of work. In 1936 alone she appeared in twelve films. For the decade as a whole her performances numbered about forty—nearly all of them in the role of maid or cook to a white household. In the screen adaptation of the ground breaking Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein musical "Showboat" (1936), starring Irene Dunne, Helen Morgan and Paul Robeson, Hattie sang with Dunne and Robeson as well, where the two sang special material written especially for the film by the team of Kern/Hammerstein.

During the 1930s Hattie wisely befriended many of Hollywood’s top actors: Joan Crawford, Tallulah Bankhead, Bette Davis, Shirley Temple, Henry Fonda, Cary Grant, Ronald Reagan, Olivia De Havilland, and Clark Gable, who went to bat for her, insisting she be cast in their films and from then on Hattie never lacked work.

Hattie won the role of Mammy in "Gone with the Wind" (1939) over several rivals. Her salary for "Gone with the Wind" was to be $450 a week, which was much more than what her real-life counterparts could hope to earn. Yet all of the film's black actors, including McDaniel, were barred from attending the film's premiere, aired at the Loew's Grand Theatre on Peachtree Street in Atlanta, Georgia. Clark Gable threatened to boycott the premiere in Atlanta because McDaniel was not invited, but later relented when she convinced him to go.

Hattie's performance as Mammy in "Gone with the Wind" was more than a bit part. It so impressed the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences that she was awarded the 1940 Oscar for best supporting actress, the first ever won by an African American. Hattie's award-winning performance was generally seen by the black press as a symbol of progress for African Americans, although some members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) were still displeased with her work.

Hattie spent much of 1940 touring the country as Mammy, and in the following year she appeared in three substantial film roles, earning no less than $31,000 for her efforts. She was married, for a third time, to James L. Crawford in 1941.

The mid-1940s brought trying times for Hattie, who experienced a heart-wrenching false pregnancy in 1944 and soon after became the victim of racist-inspired legal problems. The actress found herself in a legal battle over a system in Los Angeles that limited the land and home ownership rights of African Americans. Having purchased a house in 1942, Hattie faced the possibility of being thrown out of her home. She was one of several black entertainers who challenged the racist system in court, however, and won.

Still, throughout the 1940s a growing number of activists viewed Hattie and all she represented as damaging to the budding fight for civil rights. NAACP president Walter White pressed both actors and studios to stop making films that tended to ridicule black people, and he singled out the roles of Hattie McDaniel as particularly offensive. In response McDaniel defended her right to choose whichever roles she saw fit, adding that many of her screen roles had shown themselves to be more than equal to that of their white employers.

By the late 1940s McDaniel found herself in a difficult position. She found her screen opportunities disappearing even as she suffered insults from progressive blacks. After her third marriage ended in divorce in 1945, Hattie became increasingly depressed. She pulled herself together, however and landed a starring role in 1946's "Song of the South".

In 1947 Hattie won the starring role of Beulah on "The Beulah Show", a CBS radio show about a black maid and the white family for whom she worked. When Hattie took over the role as Beulah, she became the first black performer to star in a radio program intended for a general audience. The program was generally praised by the NAACP and the Urban League, along with the twenty million other Americans who listened to it every evening at the height of its popularity in 1950.

Hattie's last marriage, to an interior decorator named Larry Williams, lasted only a few months. In 1951 she suffered a heart attack while filming the first few segments of a projected television version of "The Beulah Show". By summer she was diagnosed with breast cancer. Hattie died in Hollywood, California, on October 26, 1952.

In her will, Hattie wrote, "I desire a white casket and a white shroud; white gardenias in my hair and in my hands, together with a white gardenia blanket and a pillow of red roses. I also wish to be buried in the Hollywood Cemetery." Hollywood Cemetery's owner at the time, Jules Roth, refused to allow her to be buried there, because, at the time of McDaniel's death, the cemetery practiced racial segregation and would not accept the remains of black people for burial. Her second choice was Rosedale Cemetery (now known as Angelus-Rosedale Cemetery), where she lies today.

Hattie willed her Oscar to Howard University, but the Oscar was lost during the race riots at Howard during the 1960s. It has never been found.

Since her death, McDaniel has been posthumously awarded two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Additionally, in 1975, she was inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame. A well-received biography on her life was published in 2005—Hattie McDaniel: Black Ambition, White Hollywood, by Jill Watts. The following year, she was honored with a commemorative U.S. postage stamp.

* * * * * *

DID YOU KNOW that (a) the human "Mammy" character in the Tom & Jerry cartoons was based on Hattie? This human supporting character was best remembered for shouting "THOMAS!" very loudly. And (b) Hattie became the first African-American to attend the Academy Awards as a guest, not a servant. Her salary for the film was $1,000 a week. Hattie McDaniel appeared in over 300 movie roles but was officially credited with only 87.

Feature Movies:

-

Love Bound (1932)

-

Impatient Maiden (1932) as Injured Patient (uncredited)

-

Are You Listening? (1932) as Aunt Fatima - Singer (uncredited)

-

The Washington Masquerade (1932) as Maid (uncredited)

-

The Boiling Point (1932) as Caroline the Cook (uncredited)

-

Crooner (1932) as Maid in Ladies' Room (uncredited)

-

Blonde Venus (1932) as Cora, Helen's Maid in New Orleans (uncredited)

-

The Golden West (1932) as Mammy Lou (uncredited)

-

Hypnotized (1932) as Powder Room Attendant (uncredited)

-

Hello, Sister (1933) as Woman in Apartment House (uncredited)

-

I'm No Angel (1933) as Tira's Maid-Manicurist (uncredited)

-

Goodbye Love (1933) as Edna the Maid (uncredited)

-

Merry Wives of Reno (1934) as Bunny's Maid (uncredited)

-

City Park (1934) as Tessie - the Ransome Maid (uncredited)

-

Operator 13 (1934) as Annie (uncredited)

-

King Kelly of the U.S.A. (1934) as Black Narcissus Mop Buyer (uncredited)

-

Judge Priest (1934) as Aunt Dilsey

-

Imitation of Life (1934) as Woman at Funeral (uncredited)

-

Flirtation (1934) as Minor Role (uncredited)

-

Lost in the Stratosphere (1934) as Ida Johnson

-

Babbitt (1934) as Rosalie, the Maid (uncredited)

-

Little Men (1934) as Asia (uncredited)

-

The Little Colonel (1935) as Mom Beck

-

Transient Lady (1935) as Servant (uncredited)

-

Traveling Saleslady (1935) as Martha Smith (uncredited)

-

China Seas (1935) as Isabel McCarthy, Dolly's Maid (uncredited)

-

Alice Adams (1935) as Malena Burns

-

Harmony Lane (1935) as Liza, the Cook (uncredited)

-

Murder by Television (1935) as Isabella - the Cook

-

Music Is Magic (1935) as Hattie

-

Another Face (1935) as Nellie - Sheila's Maid (uncredited)

-

We're Only Human (1935) as Molly, Martin's Maid (uncredited)

-

Next Time We Love (1936) as Hanna (uncredited)

-

The First Baby (1936) as Dora

-

The Singing Kid (1936) as Maid (uncredited)

-

Gentle Julia (1936) as Kitty Silvers

-

Show Boat (1936) as Queenie

-

High Tension (1936) as Hattie

-

The Bride Walks Out (1936) as Mamie - Carolyn's Maid

-

Postal Inspector (1936) as Deborah (uncredited)

-

Star for a Night (1936) as Hattie

-

Valiant Is the Word for Carrie (1936) as Ellen Belle

-

Libeled Lady (1936) as Maid in Grand Plaza Hall (uncredited)

-

Can This Be Dixie? (1936) as Lizzie

-

Reunion (1936) as Sadie

-

Racing Lady (1937) as Abby

-

Don't Tell the Wife (1937) as Mamie, Nancy's Maid (uncredited)

-

The Crime Nobody Saw (1937) as Ambrosia

-

The Wildcatter (1937) as Pearl (uncredited)

-

Saratoga (1937) as Rosetta

-

Stella Dallas (1937) as Maid

-

Sky Racket (1937) as Jenny

-

Over the Goal (1937) as Hannah

-

Merry Go Round of 1938 (1937) as Maid (uncredited)

-

Nothing Sacred (1937) as Mrs. Walker (uncredited)

-

45 Fathers (1937) as Beulah

-

Quick Money (1937) as Hattie (uncredited)

-

True Confession (1937) as Ella

-

Mississippi Moods (1937)

-

Battle of Broadway (1938) as Agatha

-

Vivacious Lady (1938) as Hattie - Maid at Prom Dance (uncredited)

-

The Shopworn Angel (1938) as Martha

-

Carefree (1938) as Hattie (uncredited)

-

The Mad Miss Manton (1938) as Hilda

-

The Shining Hour (1938) as Belvedere

-

Everybody's Baby (1939) as Hattie

-

Zenobia (1939) as Dehlia

-

Gone with the Wind (1939) as Mammy - House Servant

-

Maryland (1940) as Aunt Carrie

-

The Great Lie (1941) as Violet

-

Affectionately Yours (1941) as Cynthia

-

They Died with Their Boots On (1941) as Callie

-

The Male Animal (1942) as Cleota

-

In This Our Life (1942) as Minerva Clay

-

George Washington Slept Here (1942) as Hester, the Fullers' Maid

-

Johnny Come Lately (1943) as Aida

-

Thank Your Lucky Stars (1943) as Gossip in 'Ice Cold Katie' Number

-

Since You Went Away (1944) as Fidelia

-

Janie (1944) as April - Conway's Maid

-

Three Is a Family (1944) as Maid

-

Hi, Beautiful (1944) as Millie

-

Janie Gets Married (1946) as April

-

Margie (1946) as Cynthia

-

Never Say Goodbye (1946) as Cozie

-

Song of the South (1946) as Aunt Tempy

-

The Flame (1947) as Celia

-

Mickey (1948) as Bertha

-

Family Honeymoon (1948) as Phyllis

-

The Big Wheel (1949) as Minnie

Short subjects:

-

Mickey's Rescue (1934) as Maid (uncredited)

-

Fate's Fathead (1934) as Mandy - the Maid (uncredited)

-

The Chases of Pimple Street (1934) as Hattie, Gertrude's Maid (uncredited)

-

Anniversary Trouble (1935) as Mandy, the Maid

-

Okay Toots! (1935) as Hattie - the Maid (uncredited)

-

Wig-Wag (1935) as Cook (uncredited)

-

The Four Star Boarder (1935) as Maid (uncredited)

-

Arbor Day (1936) as Buckwheat's Mother

-

Termites of 1938 (1938)